Sunday, August 31, 2025

Saturday, August 16, 2025

Turkish Films | NH25 Wrocław, Poland

NH25 New Horizons International Film Festival Wrocław, Poland

The 15 Best Turkish Movies of All Time

Turkish cinema was not well known worldwide until the late 90s. With the rise of the new generation of young directors who were mostly categorized under the name of “New Turkish Cinema”, it has gotten more attention. But there are also other important films in Turkish cinema history that deserve a deeper look. Here is the list of 15 best Turkish movies of all time.

15. Hayat Var (My Only Sunshine)

The singular master of New Turkish Cinema, Reha Erdem has demonstrated his skill of creating his own cinematic universe several times. His depressing coming-of-age story “Hayat Var” belongs to his dreamlike but not surreal, imaginary but also realistic world by all means.

A 14-year-old girl who lives in a rambling shack by the Bosphorus with her small crook father and her bedridden, rude, and hateful grandfather, Hayat is a typical Reha Erdem heroine. She is young, full of life, has problems with her surroundings, and dreams of escaping hopelessly.

Istanbul incorporates heaven or hell, and is vital for the discourse of “Hayat Var”. This metropolis may be like heaven for a wealthy one, but for the poor people like Hayat and her family, it’s full of suffering and sadness. Erdem triumphantly uses this characteristic of the city to show how it suffocates Hayat in her loneliness and poverty.

As the dark side of the chaotic city leaves her breathless, her inner call for revolt rises more and more. This rebellious sensation rises throughout the film, and in the end, it reaches an impressive climax. With that, you can also feel the relaxation that Hayat gets, with the help of Erdem’s masterful directorial skills.

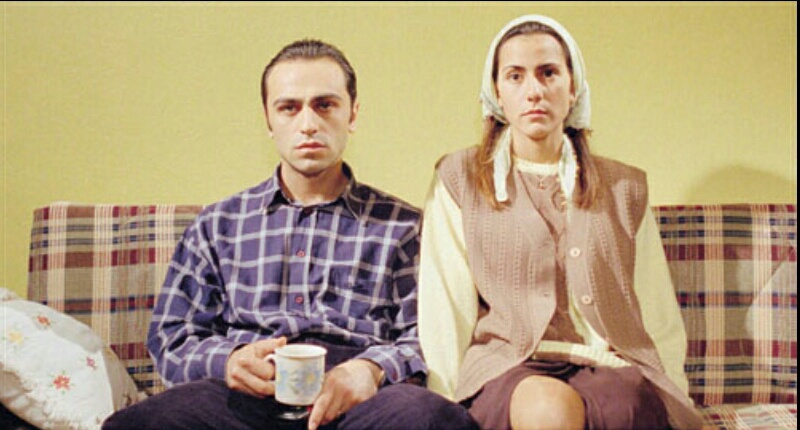

14. Gelin (Bride)

“Gelin”, which is the first part of Lüfi Ö. Akad’s “The Immigration Trilogy”, focuses on the struggle of acclimatization to a new life after moving from a small, conservative, religious Anatolian town to the big, modern city of Istanbul.

Immigration is a complex phenomenon in Turkish since the 1950s; it’s caused serious problems for both big towns and small cities that mostly consist of many villages. In his trilogy, Akad, who is also Yılmaz Güney’s mentor, examines this phenomenon both sociologically and psychologically.

As well as in every film of the trilogy, the main character of “Gelin” is a woman. This is not an incidental selection, for sure. The lead character is used for mirroring the conflict between modernism and conservatism. The family that moved to Istanbul to earn better living conditions is just in the middle of this distortion.

While the men run a grocery store as small capitalists, in their private area they live just like they did before. The bride, named Meryem, played by famous actress Hülya Koçyiğit, is never permitted to go out by the other members of the family, due to their conservative practices. This pressure peaks when Meryem’s little son gets seriously ill. The only goal of the family is earn as much as they can, so they prefer to invest in business instead of spending their funds for the boy’s treatment.

Akad cruelly displays the result of non-systemic immigration, which has been a major problem for Turkey for years. In fact, the conflict between modernism and conservatism, which especially takes place in big cities, exists all throughout the short history of the Turkish Republic. The accomplishment of “Gelin” to examine this important phenomenon in all its dimensions makes it an unforgettable slice of life seen on screen.

13. Uzak (Distant)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s first Grand Prix victory at Cannes – with the second one being “Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da” – “Uzak” deals with a time period where a young man named Yusuf moves to Istanbul and lives with a relative for some time. I intentionally use the word “period” instead of “story”, because this film is more about a period, a sense, than a distinct storyline.

Director Ceylan is also a photographer, and sets every fixed frame of the movie meticulously to reflect the sense of young man’s effort to exist in a big city. Yusuf frequently enters the frames that patiently show different parts of Istanbul. The relationship between the camera and the actor successfully symbolizes the relationship between the city and the young man.

Yusuf also faces the problem of miscommunication in Istanbul while struggling to settle in. This problem that can be seen between characters, and also between the characters and the city, is the main subject of the narrative level of “Uzak”. Ceylan’s usage of the city as an individual adds a new and poetic layer to his minimalist masterpiece, which made him an internationally-acclaimed filmmaker.

12. Bereketli Topraklar Üzerinde (On Fertile Lands)

Erden Kıral’s long-banned and long-lost film deals with three workers who left their village to earn their living on the most fertile cultivated area of Turkey called Çukurova. These naive, gracious, hardworking men face the grinder mechanism of agricultural production there.

Kıral’s approach, which focuses on the conditions and relations in the production area, differentiate “Bereketli Topraklar Üzere” from the generic style of Turkish cinema, which is mostly character-based. But this choice certainly does not make the characters superficial. The balance that was kept by the director, between the individual stories and the situation of the entire working class, forms the strongest aspect of the film.

The episodic format of the film helps Kıral to raise the tension through the worker’s journey that ends tragically in a wonderfully shot climax. “Bereketli Topraklar Üzerinde” stands as the most integrated film about the routinization of work in industrialized agriculture, the rough working conditions, and the despair of working class.

11. Adı Vasfiye (Her Name is Vasfiye)

A young writer suffers from not having an interesting story to write about, and hears about a singer named Sema Şimşek. Someone tells him her actual name is Vasfiye and her story is really worth writing about. As the writer investigates her past, the complicated story of the film unfolds.

Although the title character is a woman, the film itself is not just about her. While composing one of the most complex female characters in Turkish cinematic history, director Atıf Yılmaz also focuses on the male view of women in Turkish society.

“Adı Vasfiye” is told by four different men throughout the film. Each man describes Vasfiye as a disparate woman; coquette, virtuous, a daydreaming housewife, a widow. As the scenario leaps from one man’s memory to another’s, the audience inevitably questions the perception of reality.

Yılmaz’s brilliant storytelling technique sways between fantasy and reality, making “Adı Vasfiye” a confusing, dreamlike experience, and also a strict criticism of man’s practice of identifying woman through his own point of view.

10. Sevmek Zamanı (Time of Love)

Metin Erksan’s almost experimental melodrama “Sevmek Zamanı” tells a strange story. A poor house painter sees the portrait of a young lady while working in a luxurious mansion, and falls in love with her without knowing even her name.

After awhile, the painter and the young lady meet, but he refuses her, claiming he’s not in love with her; the portrait is what he truly loves. Thus, the film transforms into an interesting battle between reality and the semblance of reality, and instead of a typical commercial romance, it tells an ordinary love story.

Indeed, “Sevmek Zamanı” deals with love as a phenomenon and claims that a person does not need another person to fall in love; it’s all about himself or herself. Erksan’s sophisticated approach to romance is ahead of his time, even for world cinema.

This unique combination of thought-provoking themes and stylish black-and-white cinematography makes “Sevmek Zamanı” a one-of-a-kind movie. It certainly deserves to be on the same page as the arthouse romances of European cinema, like those of Antonioni or Visconti.

9. Tepenin Ardı (Beyond the Hill)

Emin Alper’s allegorical debut feature film focuses on a global issue, otherization with a local point of view, and turns its simple storyline into a tough criticism of policies of the Turkish government, as well as other states.

A retired public officer moves to the countryside and enjoys his days, doing agricultural activities. But he has some serious problems with the local people, and continuously argues with them. One day, while the family of the retired officer visits him, a goat owned by locals trespasses on his land and a series of events begin, triggering a battle between both sides.

Thanks to Alper’s storytelling skills, thought-provoking script, flawless editing, thriving usage of western iconography, and downbeat but nonstop rhythm that reaches a funny and disturbing finale, “Tepenin Ardı” deserves to be respected as one of the best debut films of Turkish cinema; maybe even the the best.

Also allegorical, the genre-denying narrative of the film says a lot about how mankind – as well as governments – creates enemies for itself from others without even knowing anything about them.

8. Kosmos

Reha Erdem’s mystic fairy tale “Kosmos” takes its title from the main character, which is one of the most unique ones in Turkish cinematic history. We see Kosmos running away from something or someone in the snow in the opening scene, and in the next sequence, he saves a little child who is about the drown in a river.

As the film goes on, Erdem introduces Kosmos as a big-hearted dervish/philosopher who symbolizes the soul of nature. In the border city in which he takes shelter, he defends the goodness of nature against the polluted mankind. He steals to help the needy, and heals sick people with his supernatural powers.

When he is asked of what he wants, he replies: “I want love.” Against Kosmos, Erdem places law enforcers as an indicator to show how far humankind has gone away from nature. Authorities pursue him as a threat to the so-called civilization, so Kosmos must move away.

“Kosmos” includes all of Erdem’s trademarks, including the brilliant visualization of nature, a rich audio track at its best, a well-written script, and amazing performances by the actors, in an influential ode to nature and purity.

7. Yol (The Way)

The 1982 Cannes Film Festival was one hell of a time for political cinema. “Missing” by Costa-Gavras and “Yol”, which was co-directed by Yılmaz Güney Şerif Gören, shared the Palme d’Or, as the latter also won the FIPRESCI prize.

“Yol” tells the the stories of prisoners who return to their towns on furlough. While they travel throughout the whole country, the audience witnesses the aftermath of the 1980 Turkish coup d’état. This destructive event turns Turkey into a gigantic prison. Wherever the prisoners go, they don’t feel free. Not just the government but authorities, also traditions of the rural Anatolian lifestyle, put more burden on their shoulders with every step they take.

In addition to its political intensity, “Yol” is also about how to be a man under oppressive traditions. The characters earn everything they have, and establish their lives with the help of the advantage of being a man in Turkey. But these importances imputed to manhood are also the reason for their hellish suffering.

Yılmaz Güney’s masterly writership makes “Yol” is a detailed, rich, depressing, and rough portrait of Turkish society after the 1980 coup. Just like the junta regime turned people’s lives into hell, directors persecute the audience in their comfortable seats and make them feel all the pain and misery seen on the screen every single second.

6. Susuz Yaz (Dry Summer)

The Golden Bear winner of the 1964 Berlin Film Festival, “Susuz Yaz” is the first international success in Turkish cinematic history. In a period where Turkish cinema mostly produced shallow, profit-oriented romances, director Metin Erksan took the melodramatic form of his contemporaries to a higher level by adding a strong political subtext to it.

The film basically tells a class struggle story that takes place during a dry rural summer. As a consequence of hot and dry weather conditions, farmers living in the village can’t water their fields. The owner of the only land with a spring doesn’t let the other farmers use the water, and both sides get into a conflict about the usage of a natural resource.

In this manner, this conflict turns into a property dispute, which is one of Erksan’s favorite subjects. In addition, the director uses the obsession of the landowner to seduce the young and charming wife of his brother, who takes sides with the farmers, to strengthen this property issue.

With the help of well-crafted, sharp black-and-white imagery that makes the audience feel all the heat and bad working conditions to the bone, Erksan’s “Susuz Yaz”, recently restored by the World Cinema Foundation, is a breakthrough film that created a social realist legacy for the next generation of filmmakers.

5. Masumiyet (Innocence)

Zeki Demirkubuz, in his masterpiece “Masumiyet”, reproduces the classic Turkish melodrama with his utterly dark style. The main character, Yusuf, who is afraid of starting a new life, doesn’t want to get out of prison after completing his sentence. However, bureaucracy obliged him to do so.

While spending his time without knowing what to do, Yusuf meets a mysterious woman in a hotel where he stays, and falls in love with her. She is a prostitute and lives with her obsessive lover, Bekir, in the same hotel. Yusuf begins to observe the lives of the couple, and day by day, he falls into their dark and deadly whirlpool.

The ironic title of the film refers to a world where nobody is completely innocent or guilty. They live their lives as destiny offers them. Demirkubuz was highly influenced by writers like Dostoevsky, Sartre, and Camus, and is an expert on reflecting the dark side of the human mind to the screen. In his second feature “Masumiyet”, he show his abilities. In the hollow world of losers and aimless people, he creates one the darkest melodramas in cinematic history.

A 7-minute long monologue sequence where Bekir, played by famous actor Haluk Bilginer, tells Yusuf about his past with the prostitute Uğur is one of the most unforgettable scenes of Turkish cinema. This monologue also turns into a prequel to “Masumiyet” – “Kader” (Destiny), released nine years later, which is another masterwork by Demirkubuz.

4. Umut (Hope)

Frequently compared to Italian Neorealist classics, “Umut” points out a new era of legendary actor/director Yılmaz Güney’s career. At the beginning his acting career, he mostly played leading male characters in commercial adventure films.

After directing and playing in more serious pictures, he shot “Umut” in 1970, which is a pure social realist drama without any melodramatic elements. This tragic masterpiece lays the foundation stones of political filmmaking in Turkey.

This situation sets a parallelism between Güney’s career and Turkish cinema history. Beloved actor Güney becomes a significant figure of the socialist movement by the late 60s, as “Umut” opens a door to the other directors who made other important political films that carried Güney’s flag forward. His track record can be seen even in the movies made today.

The importance of “Umut” for Turkish cinema is not only historical, but also artistic. The script, which tells the story of a poor carriage driver whose horse is hit by a luxurious car and dies, is perfect. With Güney’s writing and acting skills, a risky subject that could have easily been turned into a cheap tear-jerker became realistic, and with outspoken narration and world-class cinematography, it became a true revolutionist classic.

3. Kış Uykusu (Winter Sleep)

The second Palme d’Or winner from Turkey, “Kış Uykusu” basically examines the gap between the wealthy intellectuals and the poor people. Aydın, played by Haluk Bilginer, is a know-it-all and sometimes arrogant former actor. He lives with his young wife and sister in Cappadocia, a touristic Central Anatolian town, and runs a hotel there. As the three people interact with poor local people, the hotel turns into a field of contest that they face with their animosities.

Loosely based on stories from Anton Chekhov, “Kış Uykusu” is Ceylan’s more talkative work. He has proven his talent regarding movies with less dialogue in his early career. His control over dialogues mise-en-scene in “Kış Uykusu” is surprisingly riveting. It feels like he conducts his orchestra in long scenes where the characters argue with each other.

Ceylan, who is counted among the best active directors of the world, exhibits all of his skills in “Kış Uykusu”. His masterful direction, well-written dialogues, deep characters, great imagery of snowy Anatolian landscapes, and the sophisticated sociocultural study of the gap between classes in Turkish society make this film a masterclass.

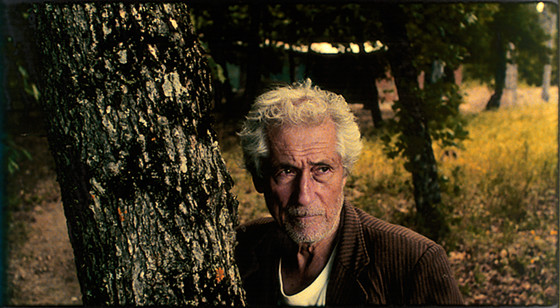

2. Anayurt Oteli (Motherland Hotel)

Main character Zebercet is the owner and manager of a small town hotel that entitles the movie. While he deals with his own loneliness and the boredom of his routines in this isolated hotel, one day, a charming woman appears. After staying for a night, she leaves and says she will be back in a week. Zebercet begins waiting for that woman who ignites him in every sense, but she never returns. Zebercet’s wait becomes a kind of torture.

“Anayurt Oteli” is a film that shows a sense of waiting, both of Zebercet himself and an entire generation that witnessed the establishment of the modernist, secular Turkish Republic in the place of the traditionalist, conservative, and religious Ottoman Empire. This huge change in the recent past caused a devastating refraction for people who lost their identities between these opposite lifestyles.

Director Ömer Kavur, who undoubtedly deserves to be described as an auteur, builds the narrative on this confusion aside Zebercet’s personal wait. His refined work results in a multi-layered masterpiece. This nightmarish existentialist psychological thriller/drama is one of the hidden gems of world cinema that waits for its time to reach a much wider audience.

1. Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da (Once Upon a Time in Anatolia)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s “Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da” begins with a murder investigation. In its marvelous opening sequence, a group of men, which includes reputable people like a policeman, a doctor, and a prosecutor, drives through the night to find a buried body in a small rural Anatolian town. As the search drags on, the investigation loses its significance. The main theme of this masterpiece comes into light; the power struggle of men in a totally corrupt system.

The influence of the literature on Ceylan’s work is not a secret. This fact is easily perceived in every single moment of the film. The depth of the characters, and the quiet but intense storyline make feel like you’re reading a great novel, and at the same time, watching one of the biggest films of modern European art house cinema.

The amazing usage of endless Anatolian steppe adds a suffocating, exit-less feeling to the intense narration. Even in the outdoor scenes, the characters, which are compulsorily integrated to this corrupt system, seem like they have nowhere to run and are trapped inside this open-air prison.

The balance of powers differs as the story unfolds, but there is never never a winner or loser in such a feeling of learned helplessness. The lifeless feeling can be read in the faces of every male character. Indeed, “Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da” is a tale of a society that is already dead, that also knows this and is waiting for its autopsy.

Author Bio: Güvenç Atsüren is a half-accountant, half-film critic from Istanbul, Turkey. His writing is published in some important websites and magazines of Turkey. He is deeply interested in world cinema.

12 Essential Films For An Introduction To Turkish Cinema

12 Essential Films

For An Introduction To Turkish Cinema

SOURCE

With the recent ‘Winter Sleep’ by filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes, many would have been surprised to hear that Turkey even had a film industry. Below is a list of 12 films to whet the appetite of any lover of film who is looking for a new taste in cinema.

Note: The films on this list are not rated in any order and have been selected as essential viewing to guide an introductory exploration of Turkish cinema.

1. G.O.R.A (2004)

A science fiction comedy, G.O.R.A is the most ambitious film to come from Turkish Cinema in terms of scope. The special effects and production design reached new levels with its record budget of $5 million for a Turkish production.

The film utilises what it lacks in comparison to the Hollywood pictures to feed its humour and challenges the notion (in Hollywood blockbusters) that extra-terrestrials only abduct westerners. The film’s biggest achievement is perhaps its accessibility and international reach to audiences, a feat that not many comedies of Turkish cinema had achieved before.

2. Komser Şekspir aka Commissar Shakespeare (2001)

A constant frustration of Turkish cinema in its 100 year history has been its struggle against censorship from the state and political lobbies. However, even more frustrating has been the censorship of tradition, the weight of history and a tendency to critique challenges to social norms.

This tender and touching story of the importance of art in dragging the reluctant to accept new identities and views is a cinematic ode to the passion the Turks have for cinema, their love of drama, their passion to be heard and their struggle to form a hybrid identity comprising of east and west nuances.

The macho lead explores the feminine, the criminals explore compassion, the corrupt authority figures find empathy and the audience, discovers a new voice through a production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, staged in an oppressive police station. This is a must see, if only to understand why Turks make the films they do.

3. Incir Reçeli aka Figs Jam (2011)

A controversial unorthodox love story, ‘Figs Jam’ tells the story of a screenwriter and the woman that literally stumbles into his life, triggering an unlikely romance. The film split audiences because of the protagonist’s reaction to a revelation by his new love.

This revelation, like this film, drags the audience and the central character into a new realm. The old ways of telling a story (in Turkish cinema) are challenged and the absurdity of being judgmental is revealed. ‘Figs Jam’ is a cinematic meditation on the Turkish experience of eastern values whilst travelling west, it is a traditional drama told in the voice of a European and wonderfully so, through the art of cinema.

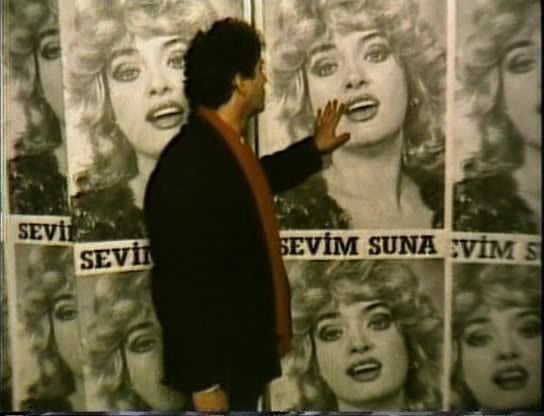

4. Sevmek Zamani aka Time to Love (1965)

A stylised and unique departure from traditional Turkish films, ‘Time to Love’ is an underappreciated gem of Turkish cinema and rests comfortably along the films of Italian maestros Luchino Visconti or Vittorio De Sica.

It tells the story of a man who falls in love with a publicity poster of a woman, who through circumstance falls in love with him. However, the protagonist is in love with her picture, not her. The film is light on dialogue and accordingly the symbolism and assured confidence of the camera communicates through cinematic poetry, taking over where meanings are no longer expressed by words.

5. Yazgi aka Fate (2001)

Staunchly independent and relentlessly uncompromising Director Zeki Demirkubuz makes films unlike any other in Turkey. ‘Fate’ is a subtle adaptation of the Albert Camus novel L’Étranger and relates the story of an anti-hero who is apathetic and without emotion to society’s expectations.

The film, the first in the filmmaker’s Tales Of Darkness trilogy is spot on with its condemnation of fate as a way to avoid personal culpability but at the same time acknowledges a now all too conventional reaction to estrangement.

6. Umut aka Hope (1970)

‘Hope’ is the story of a man, who, after losing one of his horses in an accident, sets out into the desert in a quest for a mythical lost treasure. A victim of censorship at the time, the release of the film was delayed, but the filmmaker Yilmaz Guney was a talent not to be silenced and a copy of the film was smuggled out and presented at the Cannes Film Festival.

The film is on the same page as the films of Roberto Rossellini and Cesare Zavattini and has often been compared to ‘Bicycle Thieves’ by De Sica. To this day, it stands as an example of neo realism and revolutionary cinema of Turkey.

7. Ah güzel Istanbul aka O Beautiful Istanbul (1966)

An icon of Turkish cinema Director Atif Yilmaz was renowned for the performances he drew from his actors and for his vast body of popular works. ‘O Beautiful Istanbul’ is a standout amongst them and for more reasons than one.

A dark romantic comedy contrasted with the beautiful backdrop of bustling and vibrant Istanbul the director frames the city as a character in the film and in doing so weaves a warm, charismatic tale that is as approachable today as it was then.

8. Üç Maymun aka Three Monkeys (2008)

Turkey’s official submission for the 2008 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. However it was at Cannes 2008 that the film found international praise from critics when the Director Nuri Bilge Ceylan was awarded the Best Director prize for his elegiac neo-noir detective story.

The story is light on dialogue but then again it’s not required, the cinematography is superb and expresses the anguish effectively. Coupled with a deliberate slow pace the audience is drawn in and it all amounts to a successful psychological thriller.

9. Eskiya aka The Bandit (1996)

Turkey’s hopes for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 69th Academy Awards were not realised and a nomination went begging. But then again, this film, one can sense is happy to have been a contender.

The titular character returns home from prison after 35years to find that his village has flooded. He then sets off to the city to seek revenge from the snitch that put him away. On this journey the bandit acts as wise council for a young man who wants to be a gangster, who in return assists the bandit to stay afloat in an occidental city, which is just as much a prison as it is flooded with western peculiarities.

These themes are complemented by the films cinematography, direction and narrative which dance gleefully with Hollywood action flick tropes and are coupled with eastern legends and myths that are ever so prevalent in eastern story telling. The occidental bandit could have been a contender to stem the flow of the western flood and the young man may stay afloat if he embraces the myths. However the films mediation is not on this conflict, but on the obvious . . . we are all contenders.

10. Selvi Boylum, Al Yazmalım aka The Girl With The Red Scarf (1978)

Once again director Atif Yilmaz draws a phenomenal performance from his actors. A wonderful romantic drama is woven when coupled with a standout soundtrack composed by Cahit Berkay, which is as iconic as the film itself.

However this simple story of love is not just an example of Turkish cinemas ability to tell a romantic tale. It is as much an example of the directors’ meticulous attention to detail and effective staging of mise-en-scène. Atif Yilmaz displays a faultless performance as director and finds a balance between poetry and motion, whereby the internal conflicts are voiced and the external conflicts are buried, which ultimately leads to a decision. One that the audience will share, in a finale that is up there with the greatest.

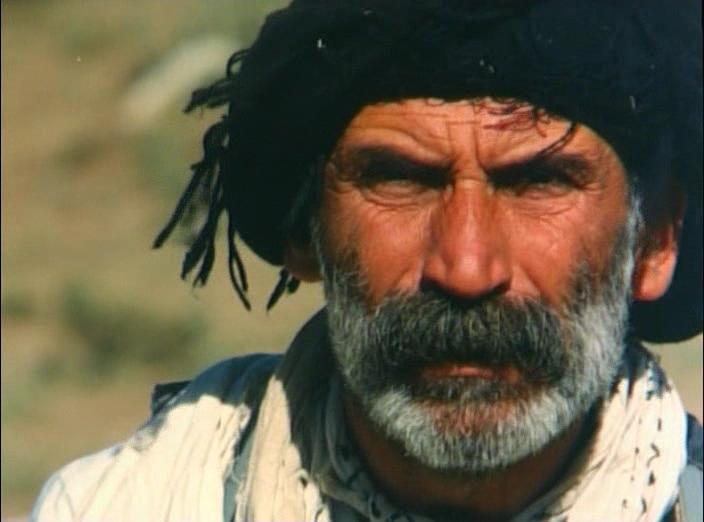

11. Sürü aka The Herd (1979)

The second film of Yilmaz Guney to feature on this list. ‘The Herd’ is perhaps not as well known as ‘The Road’ the Palme d’Or winner of 1982. However, winning awards is not the measuring stick for this list. The herd is a story of a journey. A dramatic tale emerging from a social stance and ending on an existential note.

The narrative is carried forward on a train journey. This train allows the viewer access into the interior of Turkey (much like the river in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness does in Africa) as it travels from barren villages of the east and into the developed west. On the other hand, unlike Conrad’s novel, the herd is not divided from the events and the people it encounters. With the west representing hope and the journey riddled with corruption and injustice. The film hints that the herd perhaps needs to take the journey in order to connect the good and the bad so as one can see themselves in relation to it.

Yilmaz Guney’s films normally make strong and powerful statements about Turkish society and authority in general. However, ‘The Herd’ is perhaps the most responsible and therefore the most approachable of his statements.

12. Uzak aka Distant (2002)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Distant is an outstanding piece of cinema from the director, who like Yilmaz Guney often meditates on the gulf between the city and the country. In this film the hospitality that one expects is experienced by city folk upon visiting family back at home in the village is not returned when Yusuf played exceptionally by Mehmet Emin Toprak (who sadly passed away in 2002) comes to the big city to stay with his cousin Mahmut, hopeful of breaking the drought of employment and opportunity.

The performances of the two lead actors are undeniably worthy of recognition. The character Yusuf is lonely and isolated and at times displays the same brooding existential vibe as Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle yet doesn’t need to explode with violence to communicate with the audience. The character Mahmut also lonely and isolated reminds one of Edward Norton’s character in Fight Club, career success and its material cousins cannot deliver the experience he longs for yet psychologically cannot obtain. The distance in geography, between individuals and even from art are all explored with intensity and patience, a must see and a worthy introduction to Turkish cinema.

Other worthwhile films: Journey to the Sun (1999), Motherland Hotel (1987), Feyzo, The Polite One (1978), Bitter Life (1962), Once Upon a time in Anatolia (2011), Facing Windows (2003), The Road (1982), Winter Sleep (2014), Head On (2004).

Author Bio: Agreysiren is a 35 year old from Melbourne, Australia. He currently holds a degree in International Economics and is a lifelong student of cinema. For suggestions on what to watch and latest updates and news visit https://www.facebook.com/agreysirenpics & www.agreysirenpics.wordpress.com.

Friday, August 15, 2025

Nuri Bilge Ceylan Films by Sona Karapoghosyan

All 8 Nuri Bilge Ceylan Movies

Ranked From Worst To Best [1]

Posted on by Sona Karapoghosyan [2]

According to acclaimed Turkish film critic Asuman Suner, the first signs of New Turkish Cinema refer to the 1960s. During those years, Turkish directors who were strongly influenced by Italian neorealism started to claim similarities between dictatorships of Menderes and Mussolini and direct films akin to Italian. The situation changed after the 1980 military coup when tough censorship limited the freedom of the directors for more than 10 years.

Meanwhile, there are other critics and film historians arguing that New Turkish Cinema started in the 1990s and continues up to this day. There are several directors who represent this wave to the audience worldwide and the most acclaimed of them is Nuri Bilge Ceylan.

8. Cocoon (1995)

A photographer by profession, Nuri Bilge Ceylan started directing in his late 30s. “Cocoon” was his first film and it was selected in the competition program for short films at Cannes Film Festival.

The 17-minute film introduces the audience to an elderly couple and tells the story of their break-up and reunification. At the first half of the film, they are separated and the director masterfully conveys the feeling of anguish and emptiness and even panic that the characters have. At the second half of the short, the plight changes: after the wife’s return, Ceylan puts on divine music by Vyacheslav Artyomov and the sense of loneliness fades away.

The film doesn’t have any dialogue and there is no need for them. The director, who has a perfect photographic eye, expresses everything through beautiful shots of nature that are reminiscent of those by Tarkovsky. He chose his parents as main characters, whom the audience will meet in the following movies by Ceylan. The same can be said about some locations and shots that appear in the second film of the director.

It’s interesting that during the whole film, it seems to be directed by a Russian director. But Ceylan never denies the influence of Russian culture on him, and always speaks about closeness of Russian and Turkish souls.

7. Climates (2006)

There are many movies about married couples who experince crisis in relationship or are getting devorced. While talking about such scenarios one can recall SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE (Ingmar Bergman, 1974) with its unending diolouges or FACES (John Cassavetes,, 1968) with its annoying shouts and screamings. Something completely different is captured in CLIMATES where both emotions and words are muffled.

The main characters are Isa and Bahar, who are acted by Ceylan himself and his wife Ebru. Isa in an architecture lecturer at university with an unfinished dissertation, and Bahar is working as an art director on a television series. At some point, Isa decides that they need to follow their own ways and they separate. After few months he wants to restart relations with Bahar but it’s too late, something has been broken.

As was mentioned before there are almost no dialogue between couple, which will open their thoughts and feelings to a spectator. They don’t discuss the reasons of their break-up and blame each other for things. In one of his interviews, Ceylan tries to explain why there is always a lack of expressions in his films: “The truth lies in what’s hidden, in what’s not told. Reality lies in the unspoken part of our lives… People try to protect themselves; everybody has something they want to hide. They try to hide their weak side… So it’s better without words and it allows the spectator to be more active.”

At the other extreme, it is hard to deem “Climates” as a film about marriage. Like most of the films by Ceylan, this one is also about bored and jaded intellectual who doesn’t understand what he wants from his life. His unfinished dissertation is the best indicator of his lack of motivation and unwillingness to do something. The main difference between him and Mahmud from “Distant” is that Isa hasn’t cloistered himself and continues communication with the world outside. But this makes him more vulnerable and allows him to hurt people surrounding him, Bahar in particular .

6. The Small Town (1997)

“The Small Town” is the first feature length movie of the director, which can be considered as expanded and detailed version of “Cocoon”. The similarities between these two films are obvious: same locations, plights, nature scenes, and the undeniable influence of Russian culture.

In the meantime, the film is based on memoirs of the director’s sister Emine Ceylan (“Cornfield”). Ceylan and his sister were born in Istanbul but then moved to Yenice, situated in the far west of Turkey, and the characters of the children in the movie were probably drawn from them.

The story is told from the perspective of a child and took place during the four seasons of the year. The first part is winter, which captures an ordinary school in a Turkish village. Spring is depicted through the passage of the children across the field, which also can be considered as children’s first introduction to the nature. The third and the fourth parts, summer and autumn respectively, show the time children spend with their family – parents, grandparents, and uncles, who discuss the past and the future, their problems and plans. Now children discover the world of adults with its peculiarities and difficulties.

First of all, in “The Small Town”, the director wants to show the Turkish village and the ordinary people living there, their slow and peaceful life, their daily problems, hopes and concerns, love and hatred toward hometown. Ceylan talks about one of the most disturbing problems of the Turkish community and world at large- the emptying villages that cause overcrowding in the cities.

The other theme emphasized in the film, which is very popular with directors of Turkish New Cinema, is homecoming. The theme has its equivalent in German cinema and depicts an intellectual who left his hometown to find fortune in the city, but at some point decided to come back to his roots. In the movie, it is the father of the children who came back to the village.

Almost all the events captured in the film, the characters and their problems, are more deeply examined in Ceylan’s next film- “Clouds of May”.

5. Clouds of May (1999)

“Clouds of May” is the second part of Ceylan’s Village Trilogy. Having a structure of a film within a film, “Clouds of May” has very simple plot, telling about the problems of several characters. One of them is Muzaffer, who had returned to the hometown to shoot a movie, casting his parents as actors of the film.

The other crucial character is Emin, Muzaffer’s father, who is fighting against the government, which wants to crop the forest where Emin dedicated his life. The others are Saffet, the cousin of Muzaffer who’s hoping to quit the job in the fabric of the village and find new one with a higher salary in Istanbul, and little Ali, who believes that if he manages to carry an egg in his pocket for 40 days and doesn’t crack it, the most cherished of his dreams will come true.

By choosing these characters, Ceylan wants to show the situation in a contemporary Turkish village. He depicts three generation of villagers and the differences between them. While the older one still struggles to maintain his land, the younger one dreams of fleeing to the big city with big opportunities. As it regards the youngest generation, which in the film is presented through Ali, they still believe in miracles and only time will show if they are ready to fight for their land or the process of urbanization will win.

The film is dedicated to Anton Chekhov and bears a strong influence of the Russian writer, just like the other films by Ceylan. And as the director once said regarding this reference to Chekhov: “Whatever you write, Chekhov wrote something about it: every aspect of life, every kind of character. So if you have read all of the Chekhov stories, you remember them when you write the script and you like to inject it somewhere in the script. He gives you ideas like thunder in the mind.”

4. Three Monkeys (2008)

One of the distinct traits in films by Ceylan is that he avoids shooting about politics and even if he does so, the theme is something more akin to a background for the main story, which supports the storyline and makes it more dense and interesting.

“Three Monkeys” has a special place in his filmography. It is a strong social drama about a family of three, which contains political elements and mystic aspects.

The story begins when wealthy businessman, Servet, who is entering politics, hits a pedestrian and runs away. To avoid imminent resonance in the media, he decides to ask his driver Eyup take the fall and offers him money instead. While Eyup is in jail, Servet and Hacer, the wife of the driver, start a love affair. The situation becomes more complicated when the son, Ismail, learns about the affair between his mother and his father’s boss.

The title of the movie refers to a Japanese parable about three monkeys: “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” The characters are like these apes – they decide to not pay attention to the evil that is around. As a result, they are involved in it or sometimes even cause it to happen.

Like in previous movies by the director, the silence around the events in “Three Monkeys” that shape the lives of the family members is present. They don’t discuss treachery, pain, murder or any other incident that disturbs their inner world.

Regarding the visual scenes of the film, they are perfect as always: long takes of brooding Istanbul, distant shootings, scenes in the shadow of the sun, views beyond the cell, the appearing of the ghost of a child fulfill the film with disturbance, premonition and boredom at the same time.

3. Distant (2002)

“Distant” is the last film from Ceylan’s Village Trilogy (“The Small Town” in 1997 and “Clouds of May” in 1999) and contains autobiographical elements as well. It’s a story about cousins: Mahmud is a photographer and lives in Istanbul, and the younger one, Yusuf, is from small town and has arrived to the city to find a job and temporarily lives at Mahmud’s place.

Mahmud is a person who has lost all his ideals, has stopped believing in everything, and doesn’t want to communicate with anyone. He doesn’t reply to the calls from his mother and sister, offends Yusuf, and doesn’t want to admit to his mistakes. When he accuses Yusuf of stealing his watch and then finds it in the box, he doesn’t apologize for his mistake and doesn’t even tell him that the watch has been found.

Mahmud wants him to think that his cousin doesn’t trust him. He wants to get rid of Yusuf because he reminds him of his past, the past he struggles to forget. Mahmud refuses to smoke Yusuf’s cigarettes and calls it rubbish, but these are probably the cigarettes he used to smoke when he was young. And only at the last scene after Yusuf has left, does he take his cigarettes and go back to the past for a few minutes.

The audience learns about Mahmud’s loss of ideals and meaning of life in some scenes, capturing the discussion about the death of photography. In the other scene, he decides to take a photo of the wonderful village view, but changes his mind because knows that nobody needs it. Ceylan expresses the same idea while discussing the most controversial scene of “Distant”.

The scene where Mahmud and Yusuf are watching “Stalker” by Tarkovsky and later Yusuf goes to sleep, Mahmud switches “Stalker” to a porno film. Ceylan insists that the key for this scene should be sought in the previous one when Mahmud is talking to his friends. One of them asks: “Where are your ideals? You were dreaming to direct movies like Tarkovsky.” And Mahmud puts on a film by Tarkovsky to find his ideals back, but at the end turns it off because it is easier to live without them.

In the film, Ceylan pays special attention to Istanbul. The director tries to capture the whole beauty of the city but tries to maintain the mood of Mahmud. Mahmud’s Istanbul is empty, grey, and the unstoppable snow makes us feel his desperation. “Distant” is filled with symbols such as slowly falling lampshade, a little night light, and a mouse in kitchen that Mahmud wants to catch but doesn’t dare kill.

2. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011)

“Once Upon a Time in Anatolia” is considered a turning point in the filmography of the director. The film, which received the Grand Prix award at the Cannes Film Festival, is based on true events that took place in Anatolia and was told to Ceylan by the doctor who was part of that story. What’s interesting is that the doctor himself has an episodic role in the film.

“Once Upon a Time in Anatolia” contains a few plot lines, which are tangled up in a search of the body of murdered. Police officers, a doctor, a prosecutor, and two brothers who are suspected of committing homicide are driving around the Anatolian landscape during the night to find the body as brothers can’t recall where they had dug it.

On their way, they discuss various topics, from food and health to politics and philosophy. By using this vehicle, Ceylan tries to open up the hearts of Anatolians to an ordinary Istanbulian and other people around the world. During the film, which runs approximately three hours, some essential secrets are revealed and it makes events more interesting and explicable.

As the director has grown in similar environments of slowness and the delight of nature, he easily captures the unhurried and breathtaking views of Anatolia, and tells us about power of beauty, but at the same time shows its harshness. In spite of its magical beauty, it can be extremely cruel to people, especially women. While talking about the daughter of the village official, the doctor says she is going to wilt like a flower in that severe place.

Through depicting the sameness of the environment, Ceylan heightens the feeling of unrelieved confinement of residents in the region, and the fact that the characters face difficulties to find the place the where body is buried is used to emphasize this.

On the other hand, the film is filled with many literary and cinematic references. The sophisticated gaze of cinephiles will find many tributes to Kiarostami and Tarkovsky, and for someone inspired by classical literature, it will be interesting to note similarities with Chekhov’s stories.

1. Winter Sleep (2014)

The last film (so far) directed by Ceylan is “Winter Sleep”, the second film in history of Turkish cinematography that received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It is based on two short stories by Anton Chekhov- “Good People” and “The Wife”. However, Ceylan denies the film is the adaptation of the stories.

“Winter Sleep” is a story about Aydn, a retired theatre actor who keeps a hotel in Cappadocia and lives with his young wife, Nihal, and divorced sister, Nejra. Ceylan shows how untold words and unrevealed feelings can ruin relations between people, and how this can make the love fade away.

Although the loss of ideals is a common theme for all films by Ceylan, in “Winter Sleep” the only thing that Aydn has is the ideals or maybe the idea of having ideals. “You are using your ideals and beautiful words merely for humiliating others, your ideals make you hate everybody,” Nihal says during a fight with husband. Aydn has filled the whole space with his ego and arrogance and there is nothing left for Nihal, even breathing.

Every time she wants to do something on her own, he is there, trying to interfere or help. Meanwhile, from Aydn’s perspective, the plight differs: the only thing he wants is to be beside Nihal, but his pride will never let him talk about that, and all the feelings he wishes to share – love, tenderness or unbearable pain – are hidden behind his theatrical grin.

The talented Ceylan makes his audience feel the atmosphere of “Winter Sleep” more deeply by choosing wonderful locations in which to shoot. Because of the mountains of Cappadocia, snow and lonely landscape, cold colors and the heartbreaking music of Schubert, we experience the same pain and sadness, and see the loneliness of the heroes.

In an interview, Ceylan said he considers Yasujirô Ozu as a teacher and role model, but his way of expressing relationships between characters is closer to Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni. And, of course, the influence of Chekhov should not be forgotten. Once Antonioni was asked whether his films are about crises in relationships, and he replied: “It’s about their absence”.

Meanwhile, in the stories by Chekhov, characters always find strength to say what’s in their heart. The characters of Ceylan are between these two sides, but they are falling into emptiness and apathy. But the title of his last movie has a gleam of optimism and there is still hope that one day, people will wake up from their winter sleep and find back their lost ideals, feelings and love.

Author Bio: Sona Karapoghosyan is a PhD student at the faculty of Oriental Studies, YSU. Currently she is working on several film projects and writing dissertation on Turkish Cinema.

[1] Posted on by Sona Karapoghosyan

[1] Posted on by Sona Karapoghosyan